Have you ever been to Venice? Today, researchers study urban mobility using population-based simulations, telecommunication data, or GPS trajectories. However, our research offers a unique perspective by examining human mobility in 18th-century Venice. We used the Catastici—a Venetian register that documents the ownership, division, and use of land parcels in 1740—to model urban mobility nearly 300 years ago.

The Catastici records housing properties, including the owner, tenant, and the function of each parcel, written in Italian. With OCR techniques, we were able to apply computational methods to gain a deeper understanding of daily life in the past.

If you’re interested, you can view the project details in this Project Wiki Page. We discussed the history of ownership, including which family or entity ran the traghetti business, and the merge of two historical datasets of land parcels. In this page, I will only focus on the mobility modeling part, which was my contribution in this project.

You can find my codes in this GitHub Repository.

Origin–Destination Human Mobility Network

To explore the transportation routes and the potential usage of ‘traghetti’ in Venice during 1740, we began by analyzing the spatial distribution of land use. The catastici provides information about property functions, which we classified into meaningful categories to identify residential, commercial, and transport-related areas.

Data Classification

We systematically categorized properties based on keywords extracted from the parcel function. This classification forms the foundation for understanding Venice’s land use patterns and identifying the locations of homes, workplaces, and ‘‘traghetti’’ stations, essential for simulating human mobility.

| Category | Keywords | Description |

| Residential | casa, appartamento, casetta | Houses, apartments, residences |

| Commercial / Retail | bottega, magazen | Shops, warehouses, commercial buildings |

| Mixed Use (Residential + Commerce) | casa e bottega | Combined living + commerce properties |

| Religious / Institutional | chiesa, religious, institution… | Churches, religious, institutional… |

| Traghetto / Squero | traghetto, liberta, squero, gondola | Ferry crossings (traghetti)… |

| Unknown / Other | — | Entries not matching any of the above |

The inclusion of the ‘’’Mixed Use’’’ category reflects the tendency of Venetian residents to combine living and working spaces. Meanwhile, the ‘’’Traghetti/Squero’’’ category highlights the importance of ferries and boatyards in Venice’s unique transport system.

The classification result highlights the dense residential areas in the northern and southern regions, with commercial hubs concentrated in the central areas. The traghetti locations emphasize the city’s reliance on waterborne transportation, complementing the street networks to facilitate movement and trade.

Agent Definition

To simulate human mobility, we defined individuals (agents) as those who rented more than one spaces for both ‘’’residential’’’ and ‘’’commercial purposes’’’. Agents were identified through the following steps:

- Extracted names from both the ‘’’owner’’’ and ‘’’tenant’’’ columns in the dataset.

- Used the ‘’’owner column’’’ as a fallback when the tenant column was null.

- Defined agents as individuals who rented or owned ‘’’two or more properties’’’.

Home-Workplace Extraction

For each identified agent, we extracted one ‘’’home’’’ and one ‘’’workplace’’’. In cases where individuals rented or owned ‘’’multiple properties’’’, we randomly selected one property with residential class as their home and one property with commercial class as their workplace.

For those who rent more than 1 properties, the places with class House/Properties were labelled as home locations, while other classes were considered as work locations.

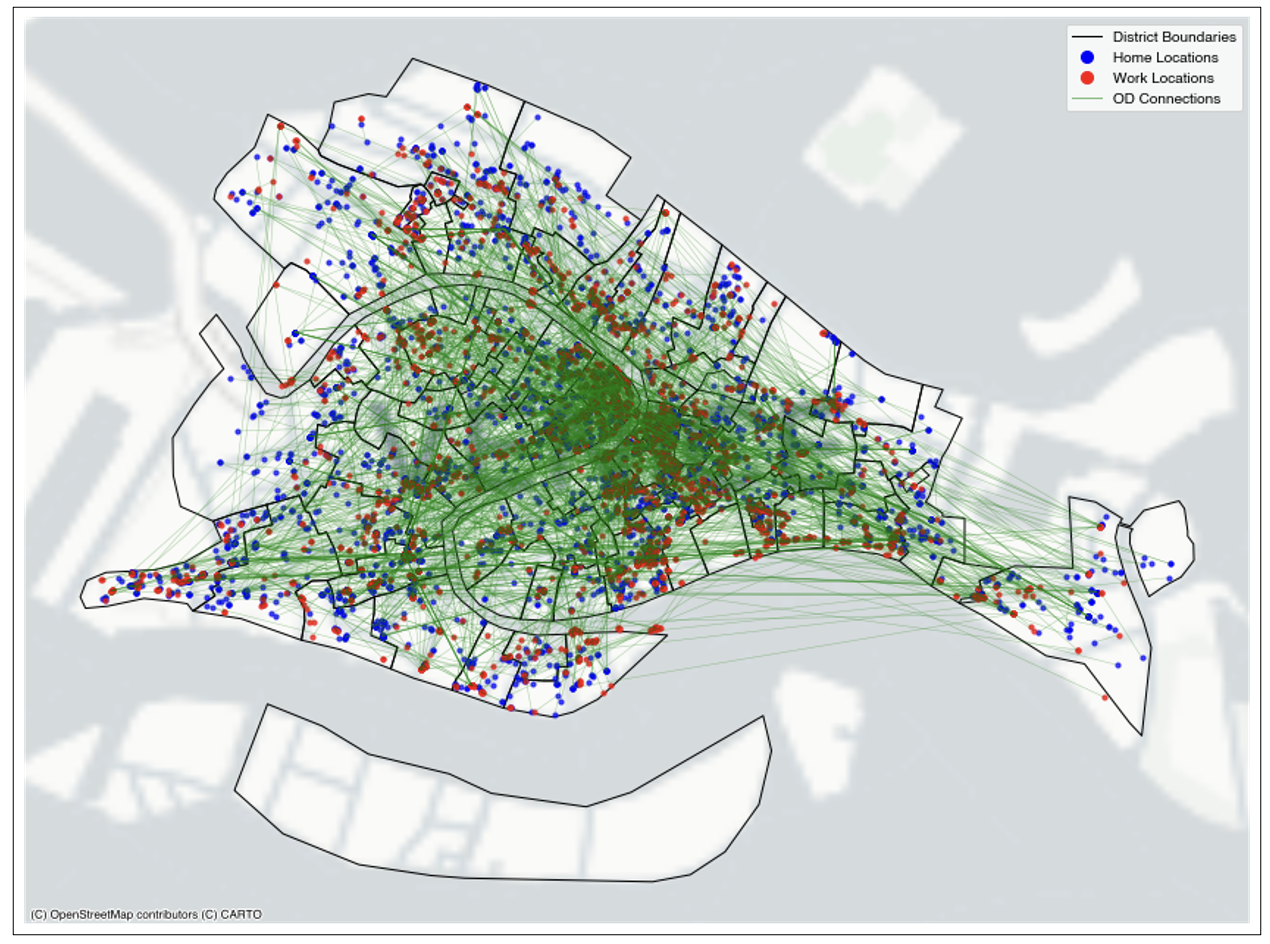

To visualize the spatial distribution of human mobility in 1740 Venice, we constructed the Origin-Destination (OD) network based on agents’ home and workplace locations. The O-D pairs analysis reveals significant spatial patterns in the home-work connections of agents in 1740 Venice.

By the links between agents’ homes and workplaces, we can observe that the central districts emerged as key hubs of activity, exhibiting a high density of destination points. This reflects the concentration commercial properties within the core areas, aligning with the urban fabric of Venice at the time.

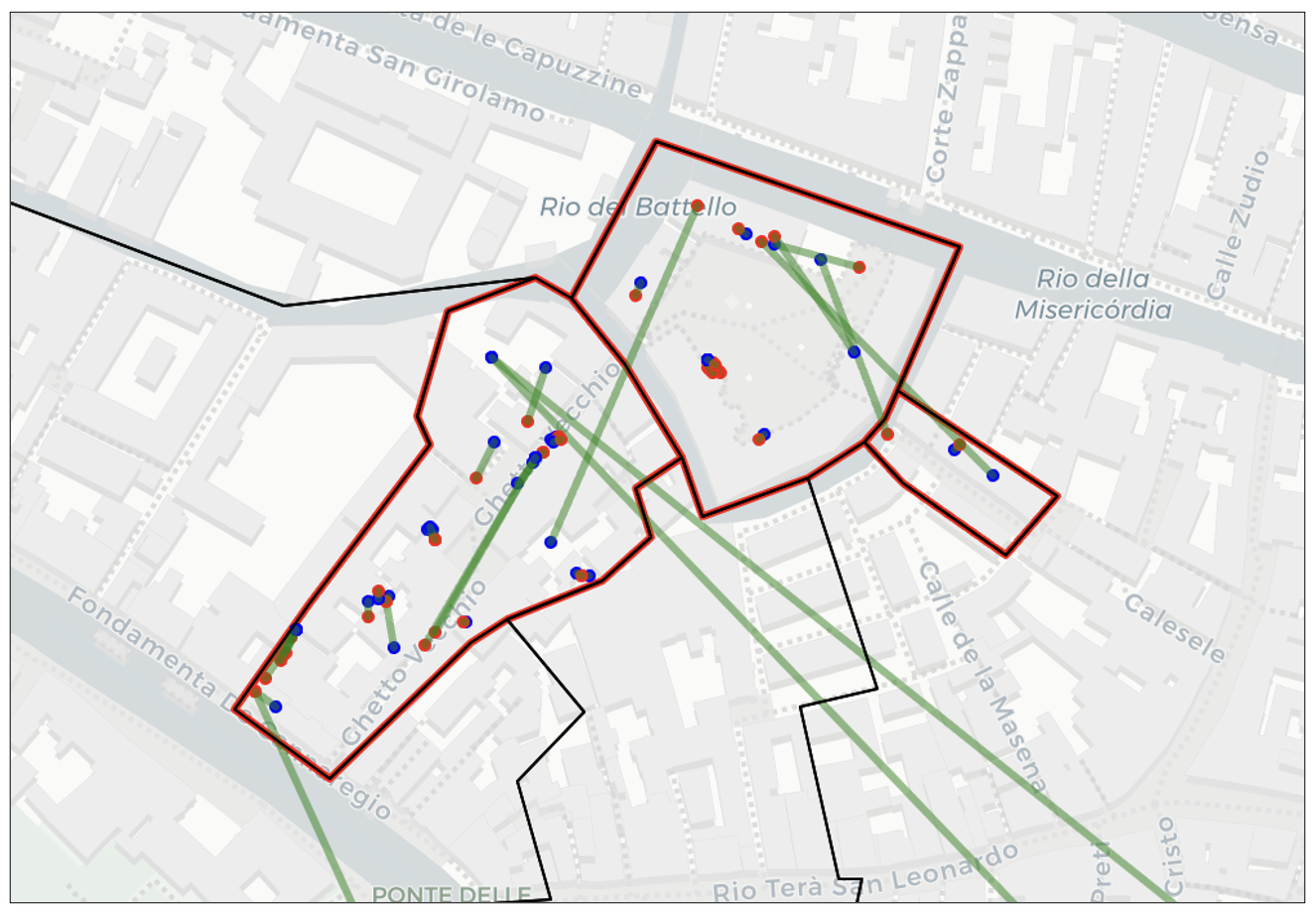

Furthermore, in the Ghetto area (Red regions above), we observe a significant number of intra-regional OD pairs, indicating localized movement within this district. This aligns with the historical context, as the Jewish population was confined to the Ghetto during specific hours of the day.

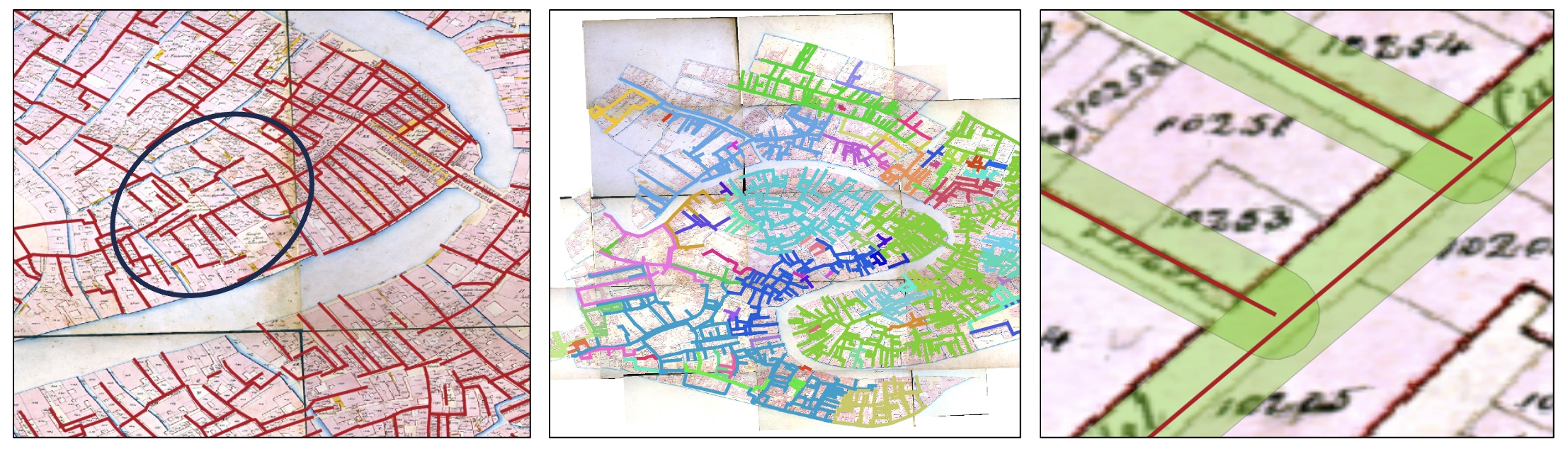

Network Geometry Engineering

To simulate how agents traveled between home and work locations, we utilized the Sommarioni 1808 road network provided by the Venice Time Machine. Although this dataset does not precisely align with the Catastici 1740 dataset the absence of road network data from 1740 necessitated its use. A comparison with the Lodovico Ughi map (1729) revealed that the road networks were largely consistent, validating its suitability for this analysis.

Challenges in Initial Network Data The raw road network data presented significant challenges, including:

Disconnected edges resulting in fragmented paths. Multiple unconnected components, preventing comprehensive route analysis. These issues posed a limitation for network-based simulations, as agents would be unable to traverse between their designated home and work locations effectively.

To address these issues and ensure a usable road network, we applied a series of geometry engineering techniques:

- Buffering and Snapping Tools: We used tools available in the ‘’’QGIS GRASS extension’’’ to connect nearby, but geometrically disjointed, segments.

- Manual Editing: Where automated methods failed, we manually edited network geometries to resolve inconsistencies and ensure logical connectivity.

- Validation: After each step, we validated the network for errors and redundancies, ensuring no excessive or artificial connections were introduced. After completing a series of geometry engineering procedures using GIS software, we obtained a fully connected street network of Venice. This process ensured that all segments are topologically correct and fully integrated, enabling seamless movement across the network.

The Origin-Destination (OD) points were then projected onto the refined street network, making them ready for subsequent analysis of human mobility patterns.

Traghetti Routes Integration

For the ‘’’traghetti’’’ routes, we digitized the primary ferry pathways using historical maps as a reference. Recognizing the strategic importance of these routes in Venice’s transport system, we assumed that all traghetti stations were interconnected, enabling seamless movement between any two ferry-serviced locations.

Through this process, we successfully transformed the road and traghetti networks into a ‘’’fully connected graph’’’. This allowed agents to travel between any two points in Venice, whether via roads or ferry routes, enabling robust simulations of human mobility and transportation patterns.

Transport Routes Modeling

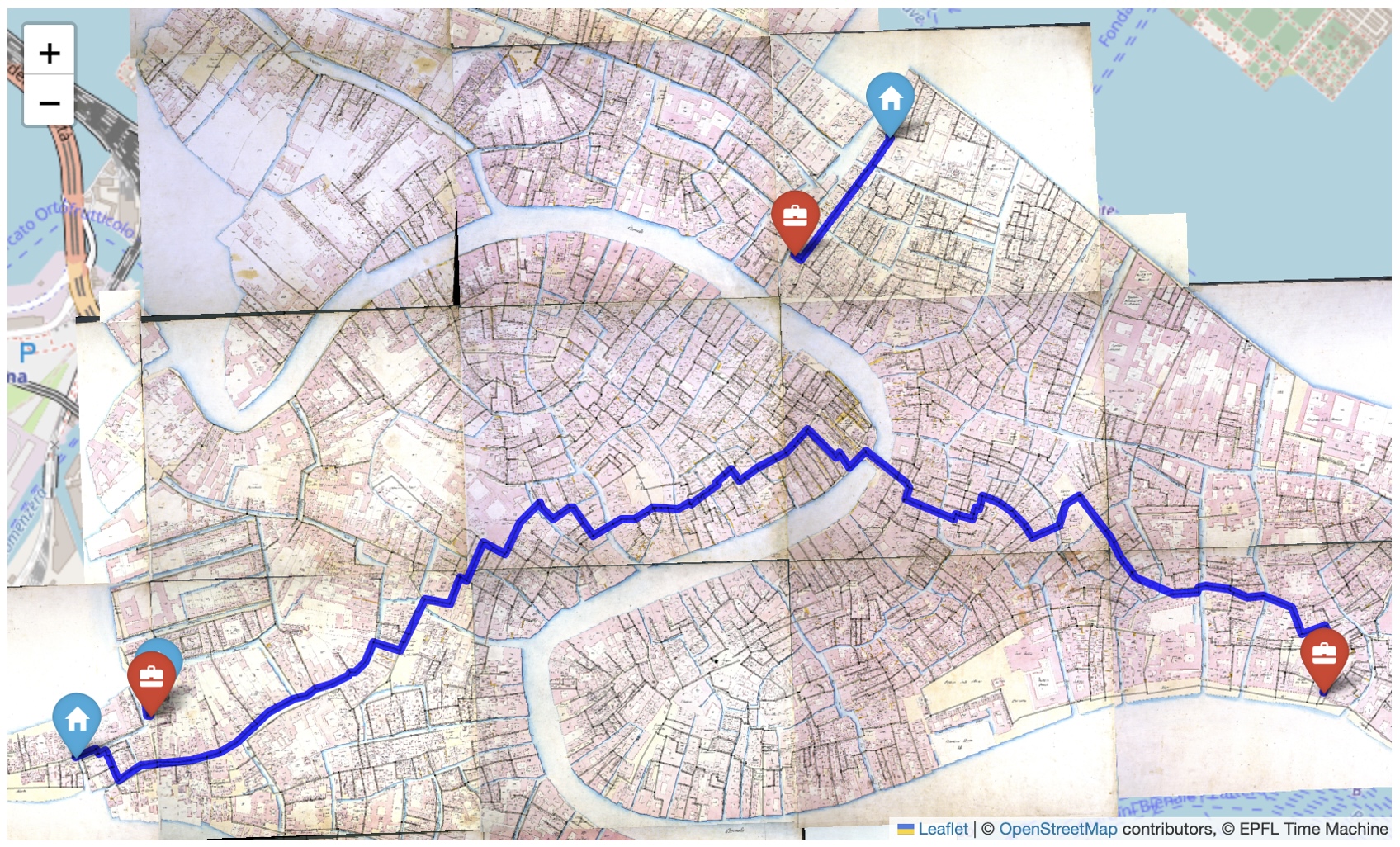

After preparing the data, we simulated agents’ movements between home and work locations using a shortest path algorithm to determine their daily commute routes. The calculated routes were then aggregated to analyze traffic flow within the road network.

The traghetti routes—the key gondola crossings in Venice—were incorporated into the network. Notably, access to these traghetti routes is only allowed at designated traghetto locations identified in the catastici of 1740. The completion of both road and canal network data provides a foundation for modeling mobility and transportation patterns in historical Venice.

We assess the functional role of the traghetti by comparing traffic flow under two scenarios:

- Using the road network only.

- Allowing agents to travel via both the road network and the traghetti network.

By analyzing the flow differences between these two scenarios, we were able to better understand the impact and importance of the traghetti in Venice’s transportation system during the 18th century.

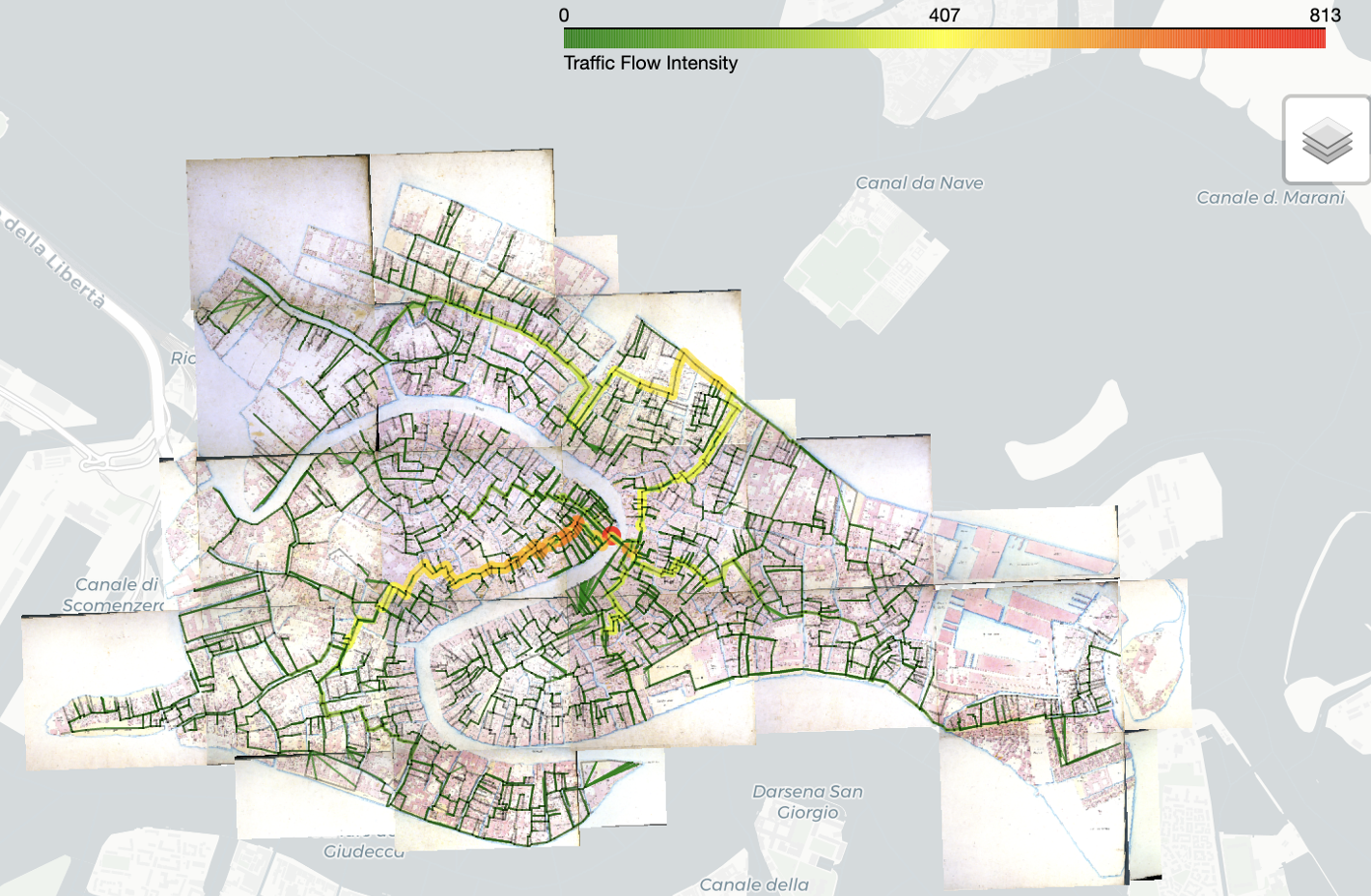

1. Using the street network only

Streets with a high concentration of shops and commercial properties, such as Ruga Vecchia San Giovanni (known for its activity even today), tend to experience significant traffic and become bustling centers of activity.

When agents are restricted to using only the street network, the connectivity of bridges plays a crucial role. A substantial amount of traffic is observed in areas near bridges, as these crossings provide the only way for individuals to traverse canals. In particular, the Ponte di Rialto, one of the most prominent bridges in Venice, becomes an exceptionally busy hub of movement.

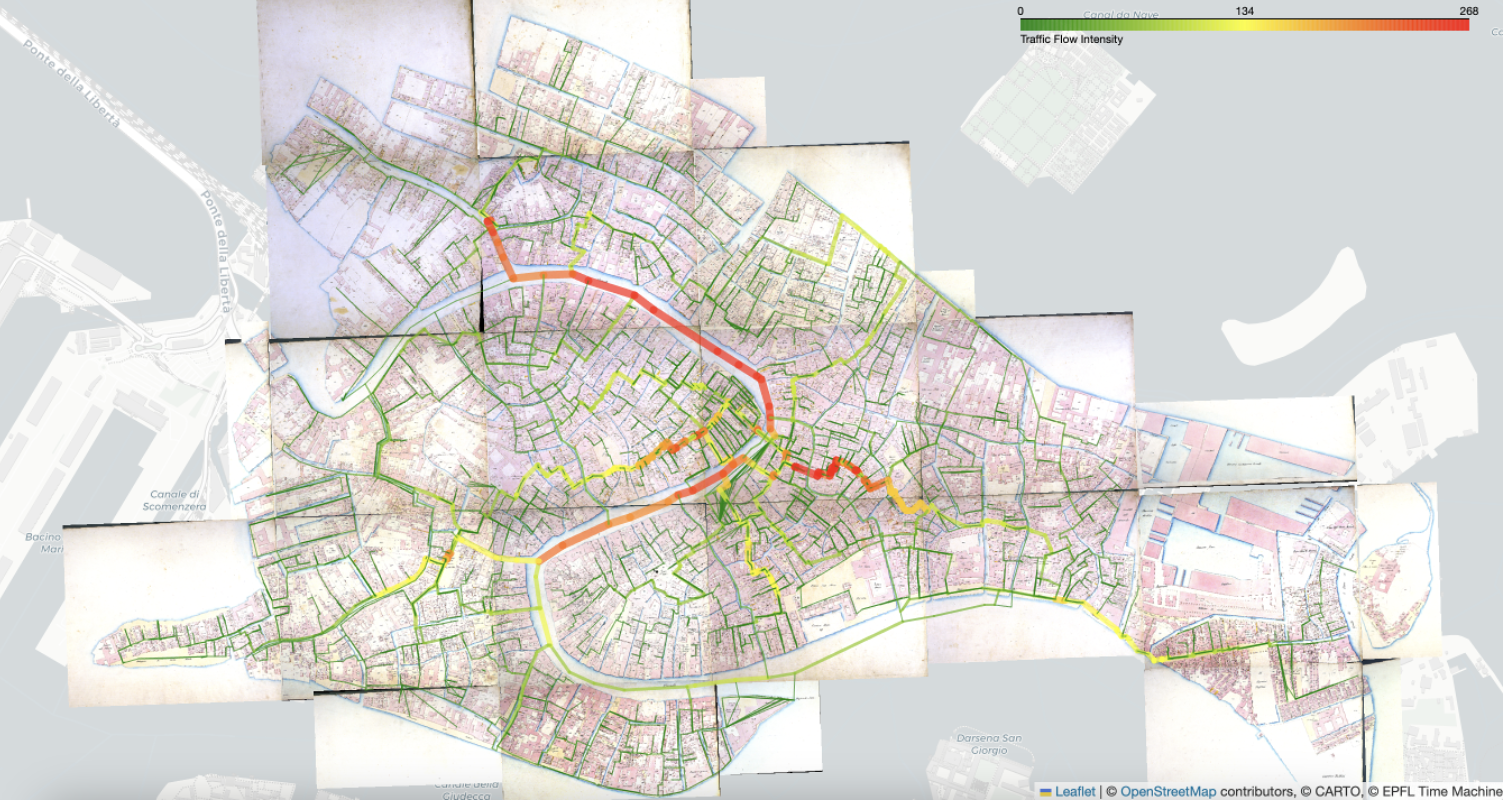

2. Allowing agents to travel via both the road network and the traghetti network

However, when traghetti are available as a transportation option, the travel patterns in Venice change significantly. A high concentration of traffic flow can be observed along the Grand Canal, reflecting its central role in facilitating movement.

In particular, residents from the northern districts—primarily residential areas—can efficiently travel across the canals via traghetti to access the commercial center for business activities. This highlights the importance of traghetti in reducing travel constraints and enhancing mobility across Venice’s unique urban system in 18th century.

You can view the Interactive Webapp Demo to explore the results and switch between different basemaps. Please note that the GitHub page might be a bit slow to load.

Conclusion

By combining the street network data and tenant information, we successfully reconstructed agent-based home and work locations, offering a rare glimpse into the mobility patterns of 18th-century Venice. Even today, obtaining such agent-level mobility data is challenging due to strict data privacy regulations. The Catastici 1740 dataset provided a unique opportunity to analyze historical mobility, highlighting the fundamental role of traghetti as critical connectors within the Venetian transport network.

This research not only demonstrates the applicability of modern data-driven methods to historical datasets but also underscores the potential of combining spatial analysis with historical records to answer questions about urban life in the past.

In the future, this approach could be expanded further by integrating additional archival data, familial archives, to refine our understanding of ownership patterns and tenant operations. Moreover, comparing historical findings with the current usage and management of traghetti could provide valuable insights into the continuity and evolution of Venice’s transport system over centuries.